Ukraine launches robot-only assault against Russian troops for first time

Kyiv pushes back military forces with remote-controlled vehicles mounted with machine guns and kamikaze drones

Joe Barnes Brussels Correspondent

24 December 2024 6:01am GMT

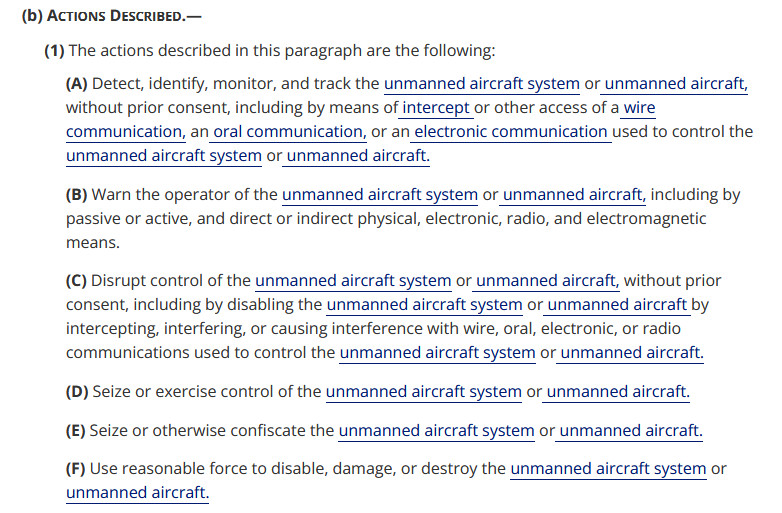

Ukraine mounted its first robot-only assault on a Russian position pushing back military forces despite being heavily outnumbered.

Kyiv’s forces used

dozens of remote-controlled vehicles mounted with machine guns as well as unmanned kamikaze drones in the raid near the Ukrainian-held town of Lyptsi, the Ukrainian military said.

The assault also

used aerial surveillance and mine-laying drones in supporting roles.

Volodymyr Dehtiarov, a representative for Ukraine’s Khartiia Brigade, said: “We are talking about dozens of units of robotic and unmanned equipment simultaneously on a small section of the front.”

With Kyiv struggling to overcome crippling manpower shortages, its armed forces have often placed faith in experimental armed robots in an attempt to turn the tide of war.

In some areas of the battlefield,

Russia has a three-to-one advantage in manpower.

Ukraine is known to have deployed

vehicles with robotic machine guns, mine layers and electronic warfare systems which minimise human involvement on the battlefield.

But

the assault by the 13th National Guard Brigade is the first example of a robot-only combined-arms manoeuvre.

The brigade is responsible for

defending a five-mile stretch of the frontline near Hlyboke, a Russian-held town in the Kharkiv region, about five miles south of the border.

Russia has four regiments attempting to advance in the area, meaning

Ukraine is countering around 6,000 troops with just 2,000 men.

Mr Dehtiarov said the assault had been a success, although The Telegraph could not independently verify the claims.

Footage released by the Brigade showed pilots operating Unmanned Ground Vehicles (UGVs) and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) from inside a command centre.

Several screens displayed live feeds of the battlefield, provided by cameras mounted on

drones and robotic ground vehicles, giving those in the command centre several views of the combat from the safety of their hidden bunker.

The pilots use controllers, which don’t look much different to those you would find with a games console, to direct the drones and UGVs and use them to Russian positions.

The UGVs, which typically look like mini-tanks with mounted machine guns, attack the positions head-on while kamikaze drones loaded with explosives crash into the Russian soldiers from above.

Other first-person view support drones hover over the battlefield transmitting live video back to the command centre to provide a bird’s-eye view, or drop mines along Russian avenues of retreat to inflict even more damage on the enemy.

The Institute for the Study of War wrote in a recent report: “Ukrainian officials have repeatedly highlighted Ukraine’s efforts to utilise technological innovations and asymmetric strike capabilities to offset Ukraine’s manpower limitations in contrast with Russia’s willingness to accept unsustainable casualty rates for marginal territorial gain.”

Mick Ryan, a former major general in the Australian army, said: “The Battle of Lyptsi is an important step in the transformation of the character of war from a purely human endeavour to something quite different in the 21st century.

“But none of the battlefield functions envisioned for uncrewed systems will be effective without the transformation of military institutions that wish to use them. This includes armies but also the civilian bureaucracies that support them.”

A similar, but smaller, example of robot warfare was reported recently from Kursk, the Russian region partially occupied by Ukrainian forces.

Kyiv’s men deployed “Fury” – a four-wheeled robot mounted with a machine gun – was used to clear a trench.

Footage of the raid appeared to show the drone weaving through a minefield before unloading a volley of shots on the Russian position.

Ukraine was the first military to form a standalone drone force – the Unmanned Systems Forces.

Volodymyr Zelensky,

Ukraine’s president, last year said the war-torn country would produce more than a million drones in 2024 to complement the new force.

But

the latest estimates suggest that the target has been well exceeded, with Ukraine capable of producing around four million drones a year annually.

Some of the latest models are fitted with fibre optic cables that prevent Russian electronic warfare jammers from severing the connection between the drones and their operators.